Ellen Nieves |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

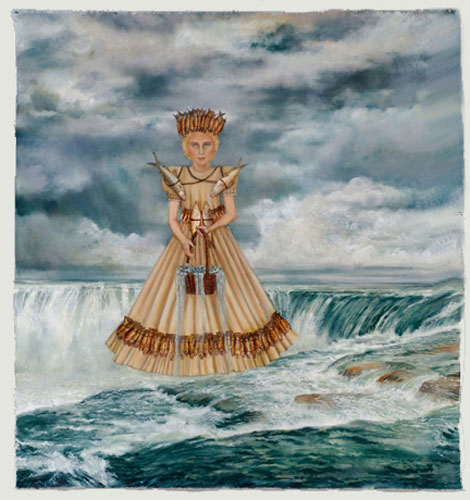

Niagra |

"Fish Until You Become The Fish"Landscapes by Olive Painter Ellen Nieves soon to be UnveiledEllen Nieves' Blue Tree | |

by Paul Smart |

At first, Ellen Nieves' new paintings seem like a major departure for the artist many know best for her exquisite landscapes - as much about atmosphere and memory as the natural world we inhabit and base our lives around up here. But then one realizes that they're actually a return to earlier themes and a culmination of all that she has learned and internalized over a long, complicated career - and life - as a painter. They're large, like all she paints, and surrealistically detailed, like dreams come to life. Each features a younger version of the artist, taken from childhood photographs, in fantastical natural settings. Ellen, as a pre-teen, floats over Niagara Falls; Ellen stands in a lush Florida jungle with an octopus at her feet; post-toddler Ellen seems to float within, or over, a sylvan Catskills creek glen. She centers a phantasmagoric galaxy of constellationlike natural phenomena, in her teen years, like a Mexican saint. "They're all about how I related to nature as a child," she says of the works, which will add up to a series of eight paintings after she finishes the two-year process of their creation. Nieves grew up in Detroit, learned about nature there and on trips to Florida, where her mother eventually settled and she got a college degree teaching art. She says that she's basically self-taught as a painter. Although her sister has ended up as a photographer, "We had to kind of invent the art angle in our family." She remembers, clearly, her first drawing: "I was four and the television had just come into homes. My parents had a Philco, and whenever my grandparents would come over, everyone would be fighting, and I noticed that the only time they would be quiet would be when they were watching the TV," she says. "I figured that if I drew the television and showed it to them when they were arguing, it would quiet them down." Wow - an early sense of the societal impact that art could have? "More like a recognition of the ability to connect to people through an image, not necessarily moving," Nieves replies. Armed with an art teaching degree, she headed for New York City and immediately discovered the hot trend of the day: Minimalism. "It was a big shock," she says of the style in which she started working, after dabbling in figures and landscapes early on, using hours in museums with a magnifying glass as her schooling for art. "But then I had a crisis...Minimalism only took me so far. It was very cerebral and didn't fulfill what I needed from art; it didn't give me the passion I want." As a result, Nieves says, she stopped painting for 15 years - then got back into it on what she thought were her own terms, at least for a while. "I started again just to have something to cover my mother's walls down in Florida that I could stand," she says with a mischievous smile. "Next thing, her friends started buying paintings." Nieves ended up setting up a business with a number of designers in Florida, and later in New York, selling work directly to buyers without gallery intermediaries. She supported herself as a painter, living and working in the West Village, where she set up an outdoor studio on her building's roof. "Those were mostly color-field paintings, done very quickly with lots of layers and washes," she says of the work from that time. "I would do them on the floor; very physical, like Pollack, working with large brushes and rollers." As before, though, Nieves says that after about seven years of growing success, she tired of what she was doing. She found herself gravitating towards the figure again, albeit from a direction that's hard to explain - but as beautiful in the telling as her art. "I came up to the Catskills with a boyfriend of the time who insisted I learn fly-fishing. I thought he was crazy, but went along," she recalls. "But then I became obsessed with it: spending as much time as I could up here in the streams, getting up at 4 a.m. to cut open fish to see what their stomach contents were, the better to fish the right fly for them. It went on like that for eight years or so." Eventually, Nieves found a husband and taught him to fish, too. They rented around Phoenicia each summer, and eventually bought a home near Boiceville. "Then one day it all came to me: the way I'd seen people who could stand in a stream and say, 'There's a fish there,' and toss the line and catch one, and 'There's a fish there,' and do it again," she remembers. "All of a sudden it was like leaving my body; I was in the entirety of the environment. I was the fish, I was the fly, I was the water in the stream, I was the current, I was the air, I was the sky. I said, 'This is amazing, and I simply cannot do this anymore.'" And Nieves hasn't fished since. "It was my first spiritual experience," she says of that moment in the Esopus years ago. "We moved up here and I started painting landscapes." We are seated in a Spartan loft in Kingston's Shirt Factory building, where a workstand and a few chairs put the focus on Nieves' new paintings. But the artist says that she's here only temporarily, ready to move back to her meadow studio in Olive so she can get back to what she likes best about painting at home: being able to sit with what she's doing with her morning tea each day, to wander out and ponder before a canvas at night. But she acknowledges how the current move helped her make this transition to the new works. Does she ever worry about losing markets when she abandons a successful style for something new? "The money has never been that important to me. In fact, whenever the money's gotten good, I've gotten bored," she says. "I like to get consumed by things." I ask about how she works. Does she paint in nature? "No," Nieves replies. She's not interested in "objectifying" the natural world. When she's out in it, she wants to be with it. In the studio, she picks pieces out of photographs and melds them together, creating what is basically a memory landscape - much as the Catskills, or many places like ours, mean different things to different people, based on their memories of similar settings from their pasts. She never sketches before painting - one of the reasons she likes to work large. How did the new works come about? "I wanted to remember what I felt like when these photographs were taken," she says, noting how an actor friend has helped her with the sorts of exercises he used to "get inside" a character. "I had a lot of imaginary friends when I was young, and this has been an opportunity to bring them back. Our memories are a reservoir that aren't tapped nearly as much as they can be." Nieves points out a blue tree in one work, talks about how she'd always wanted to do that, or about odd distortions of tree leaves that look alive. Could she have painted these works as a younger artist? "That's a very good question," she says. "I think not. I wasn't as comfortable with doing landscapes before." Nor as attuned to all these memories. For more on Nieves, visit her website at www.ellennieves.com. Click here to discuss this article in our forum. © 2007 Ulster Publishing, Inc. |